Eliot Hodgkin: A Memoir by Brian Sewell

Brian Sewell was a great friend and admirer of Eliot. In early 2015, The Estate of Eliot Hodgkin asked Sewell to write something for the forthcoming Eliot Hodgkin book. Below is a snippet of the memoir that Brian wrote. This extract is also present in the Christie’s sale catalogue Brian Sewell: Critic & Collector that will take place on 27 September 2016.

Eliot Hodgkin: A Memoir by Brian Sewell, March 2015

Mrs. Riley’s Milkweed

In the summer of 1962, walking the length of Bond Street on my way to Christie’s where I then worked, I saw in the window of Mallett, dealers in fine furniture, a strange little painting of dry stalks, dead leaves and bursting seed pods, as magical as though Salvador Dalí had revised one of Georg Ehret’s botanical studies, retaining an eighteenth century draughtsman’s accuracy of observation, but adding an hallucinatory excitement that extended the image far beyond mere realism. It had the label of Arthur Jeffress on the back, a dealer noted for his eye, was called Mrs. Riley’s Milkweed, was by Eliot Hodgkin, of whom, at that stage, I knew nothing, and was to be had for sixty guineas. Mallett could tell me nothing of Hodgkin, nor of Mrs. Riley, nor even of milkweed, but I did not care. I bought the painting and I have it still.

That desiccated sow-thistle, that bursting brimstone-wort, proved an open sesame. I had had it for a year or so when, one high summer evening, Carlos van Hasselt, then newly late of the Fitzwilliam and just appointed to the Netherlands Institute in Paris, came to dinner, saw the milkweed, and asked if Eliot was a friend. I was in awe of Carlos, master of seven languages and deep-dyed art historian, whose expertise in my chosen field of old master drawings far exceeded anything that I might learn in a lifetime; that he knew Eliot told me at once that the man who had painted Mrs. Riley’s Milkweed was no nonentity, no country cottage bumpkin with a delicate touch. With a telephone call and a taxi I found myself whisked into the presence of a painter whose Chelsea flat was a treasury of marvellous paintings by Corot and Delacroix, and of drawings by the ilk of Ingres, Degas, Fragonard and Liotard that made me ill with envy.

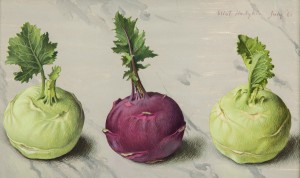

Three Kohlrabis

There was not the slightest hint of grandeur about these small masterpieces – they were a cherished part of Eliot’s domestic scene, part of his daily life and nourishment, reticent and intimate in scale, some standing in their own right as finished works of art, others perfect art historical documents that added to our perceptions of some greater work elsewhere, and that were in turn informed by awareness of those works. My fumbling and confused instincts as a magpie acquirer of scraps immediately recognised that this collection was the work of a clear eye and disciplined passion.

Not a Hodgkin painting was to be seen in this brilliant company, for Eliot was a man of modesty and claimed no place with older masters, but at last he was persuaded to open the doors of the cupboard that was his studio and show me the tiny pictures of fruit, flowers, eggs and feathers that he painted with such delight and diligence. Enchanted by two paintings of kohlrabis, purplish pink and acid green, gentled by a ground of greyish marble, I bought both. He chuckled, and told me that I had, in fact, bought one picture – he had painted five kohlrabis in a row, and when no-one bought the long narrow frieze he had sawn it in two. In time I added parsnips, turnips, lemons and a lime, the lichened tombs of churchyards and a view in Switzerland; by a stroke of luck I found large early oil paintings that Eliot thought lost, one of which, a gaudy thing of a Christmas tree, he wished had stayed so. He thought me mad to buy so many, but they gave me a direct and simple pleasure that has never diminished.